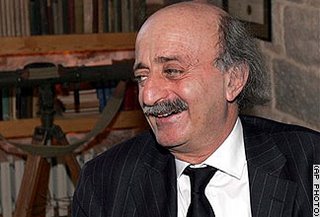

Mountain Man: The leader of Lebanon's Druze talks about the Syrian threat

Mountain Man

The leader of Lebanon's Druze talks about the Syrian threat.

BY MICHAEL YOUNG

Saturday, July 29, 2006 12:01 a.m.

MUKHTARA, Lebanon--I knew Walid Jumblatt had a passion for the history of the Second World War, but I didn't especially relish waiting for our interview under the severe gaze of Marshal Zhukov, atop a steed trampling Nazi standards. I recalled what the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa had written of Mr. Jumblatt's collection of bulky socialist realist canvases, after visiting his mountain palace at Mukhtara, where Lebanon's paramount Druze leader spends much time these days: "It was impossible for me to know if these paintings were there as an exquisite postmodern irony, or as an involuntary homage to kitsch, or because he really liked them."

Doubtless all three, since Mr. Jumblatt maneuvers dialectically, particularly in his politics. Once a prop of Syria's order in Lebanon (though the regime of Hafez Assad had murdered his father, Kamal, in 1977), he became the man most responsible for its overthrow in 2005. This betrayal earned him a sentence of death in Damascus, which is why he rarely leaves Mukhtara, from where he leads the mostly poor, mostly rural 200,000-strong Druze--like a "tribal chieftain," he once told me. It is a tribute to his political skills, but also to his hard-nosedness, that his influence far transcends the microscopic size of his community. At 57, he has been at the center of Lebanese public life for 29 long years.

It takes a good hour and a quarter to reach his home from Beirut, since Israeli aircraft have bombed the shorter route via the southern coastal road. I kill time by asking an aide about the main topic of conversation wafting though the waiting room--how to manage the thousands of Shiite refugees who have escaped south Lebanon to regions controlled by Mr. Jumblatt. The aide tells me that the relief effort is stretched to the limit, and that providing help will become a considerable problem in the coming weeks.

Mr. Jumblatt personifies patronage politics at their most essential. His is a hands-on management style, and there is sophisticated method to what can be mistakenly interpreted as Mukhtara's ambient disorder. The Druze leader runs his life with Germanic precision. His papers are well-organized, as are his publications, his collection of magazine covers, his weapons (I notice a Glock and several clips across the room), his Soviet-era regalia--even the more sinister memorabilia, such as the identity card his father had on him the day he was killed, pierced by a bullet.

As we kick into the interview, Mr. Jumblatt doesn't wait for a question. He describes the visit to Beirut the previous day of Condoleezza Rice, and particularly the international effort to set up an expanded peacekeeping force in South Lebanon to end what, by now, are two weeks of fighting. "At first they said they wanted to create a buffer zone of 20 kilometers to put in an international force. But what does that mean when Hezbollah can fire rockets over your back? Now there is a new formula: the demilitarization of the South."

Mr. Jumblatt is dubious. "Rice didn't clarify how the international force would deploy. As I've told the Americans: As long as Syria can send weapons to Hezbollah, there will be no change in the situation. Not with this regime in Damascus. We need a force that can cover all of Lebanon, like in Kosovo. Monitor the Syrian border, then talk."

The United States is not thinking about such a scheme, Mr. Jumblatt tells me. And that's why he plainly feels that American ambitions are likely to crash against the reality on the ground. If Hezbollah refuses to disarm (and it does), "then we enter a phase of all-out war, endless war, with the possibility that this will weaken the Lebanese state. Let us also remember that the Syrians a few days ago promised the Americans they would help them fight al Qaeda. This was, in fact, a backhanded warning that Syria could use al Qaeda to kill innocents in Lebanon."

(Mr. Jumblatt sounds even less confident a day later. I call him up for a reaction to the early-morning address by Hezbollah's secretary-general, Hassan Nasrallah, in which he promised to bomb deeper inside Israel. Our conversation takes place amid reports that the Israelis have suffered heavy losses in fighting for the town of Bint Jbail. "Even if Nasrallah loses positions, Hezbollah's fierce rearguard is making it increasingly difficult to set up something afterwards. I doubt we will see a multilateral force if this continues. If Nasrallah comes out victorious, he will dictate his conditions to the Lebanese state--if he still accepts the state.")

There is a strong desire for retribution in the Shiite community. Quite a few politicians, including Mr. Jumblatt, have implied that Hezbollah's abduction of two Israelis soldiers was irresponsible, which many of the group's faithful deem to be a stab in the back. This prompted Mr. Nasrallah to declare, ominously, in an Al Jazeera interview last week: "If we succeed in achieving the victory . . . we will never forget all those who supported us. . . . As for those who sinned against us . . . those who let us down, and those who conspired against us . . . this will be left for a day to settle accounts. We might be tolerant with them and we might not."

What does Mr. Jumblatt think of that threat, obviously directed against him and his political comrades? "Nasrallah was talking in the name of the Syrian regime. He thinks he's a demigod. Like [Iran's President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad he's waiting for the 12th Imam, the Mehdi. This aspect of Shiite religious mobilization can be frightening." He pauses. The phone is ringing--one of the countless times this has happened as his men ask for guidance on organizing the aid effort. Before closing, he issues instructions that trash be removed from a certain location. A lady had earlier called complaining about it.

Mr. Jumblatt's relations with Hezbollah are complex. He has been the group's most vociferous critic in recent months, and yet it was he who broke its isolation last year during the "Cedar Revolution," by helping engineer an election law preserving Hezbollah's quota in Parliament. Why? Partly to protect his own electoral stakes, partly because he thought he could profit politically from being the middleman between Hezbollah and the coalition opposed to Syria. But the arrangement later collapsed when the party refused to break with Damascus, and Mr. Jumblatt realized that his own chances of reconciling with the Syrians were negligible. An inveterate calculator, the Druze leader has surely factored easing Hezbollah's anger into his hospitality for the Shiite displaced. He even adds, for good measure: "I don't care if the refugees put up Hezbollah flags and photos. I can understand this emotional reaction." (What he doesn't say is that he's allowed this in order to lessen Shiite frustration to avert tension between Shiites and Druze.)

Given the estimated 500,000 to 700,000 people made refugees, most of them Shiites, will Hezbollah be more flexible on an overall settlement? "It makes no difference to Nasrallah," Mr. Jumblatt says. Nor should one expect much from those critical of Hezbollah's unilateralism. "We need a prominent Shiite to work with us, particularly [Parliament Speaker] Nabih Berri. Nasrallah thinks he's at the peak of his power, but you have to talk to the Shiites; you cannot allow them to be frustrated and humiliated. You have to reason with Nasrallah. The destruction we've suffered is not worth two Israeli captives, having a private army, declaring war and peace. But we need a Shiite to say this to Nasrallah."

It is the Syrians, however, who feed Mr. Jumblatt's anxieties. As he surfs the Internet at night--a pastime for which he is known to depart early from dinner parties--he can read the mounting calls in the U.S. and at the U.N. to bring Syria into a deal to control Hezbollah. For the Druze leader, this has existential implications. It could mean a Lebanese homecoming for an Assad regime that wants his head. "Syria and Iran have strengthened their cards in Lebanon today," he insists. As for the Bush administration, its Syria policy is "confused."

Starting earlier this year, Mr. Jumblatt tried to help refine the administration's strategy. On a trip to the U.S., he actively peddled the idea of regime change in Damascus, telling Ms. Rice: "The U.S. says Syrian behavior must change, but nothing will change for as long as this regime is in power. The U.S. must open a dialogue with the Syrian opposition, including the Muslim Brotherhood, which has accepted pluralism in its political program." However, all the signs from Washington are that Mr. Jumblatt will be disappointed.

Iran's role in starting the latest round of Lebanese violence is a theme Mr. Jumblatt has repeatedly raised in interviews. I play devil's advocate and suggest there is no evidence yet of direct Iranian implication--or does he know something I don't? He doesn't answer directly: "It's enough for Hezbollah to have the famous Fajr-1 and Fajr-3 rockets to show such involvement. The last I heard, these devices were not manufactured in Lebanon!" In that case had he heard that Iranians were fighting alongside Hezbollah? "Yes, we've heard rumors that Iranian Basij militiamen are participating in the fighting. I believe these stories."

In 1976, at the height of the civil war and less than a year before his assassination, Kamal Jumblatt traveled around the region to rally support against Arab endorsement of the Syrian army's presence in Lebanon. Jumblatt and his Palestinian allies were then fighting Syria. His trip started well, and he was received by top officials. But by the end of the tour, the Arab states had reached a consensus on backing a Syrian deployment, and Jumblatt suddenly found doors closing in his face. That isolation led to his eventual elimination. This explains why his son has always been sensitive to the dangers of quixotism, even as he now risks finding himself in a trap similar to his father's.

"I'm afraid that because of the chaos in Lebanon today, Syria might try to assassinate people here." Does that include him? "Yes, me, but also Fuad Siniora," the prime minister. But even if Mr. Siniora does survive, can his government do so, given that it is collaborating with the U.S. to tackle Hezbollah's arms? "Either he survives or we must accept the coup d'état fomented by Syria and Iran. That will determine whether Lebanon remains democratic."

No Jumblatt interview is complete without malicious wittiness. Asked about how the Lebanese conflict will develop in coming weeks, he says Israel's ground war will determine the outcome. "But if Hezbollah's missiles are pushed back, they will soon be here; no, they may soon be on Hamra Street," a shopping drag in the center of Beirut. "It took us a full 24 hours to negotiate the removal of a single missile from near the Pepsi-Cola factory," an enterprise just south of Beirut owned by a wealthy Druze family.

Mr. Jumblatt laughs at the absurdity of the episode, but he is making a serious point. Hezbollah can wage war from wherever it wants, regardless of its countrymen's preferences. Then he stands up and heads for an anteroom. "Let's see what the former minister wants," he sighs.

Mr. Young, a Lebanese national, is opinion editor at the Daily Star newspaper in Beirut and a contributing editor at Reason magazine. WSJ.COM Opinion Journal