Phares to the Wall Street Journal: "Secretary Rice should convene a Lebanese NGO conference to revive the Cedars Revolution"

Will Bush Lose Lebanon, Too?

November 7, 2006; Page A13, WSJ

President Bush learns tonight whether Republicans will lose control of the House, the Senate, or both. But what's a mere midterm when his administration is on the verge of losing an entire country?

That country is Lebanon. Twenty months ago, when Syrian troops were abruptly forced out in the so-called Cedar Revolution after a 29-year occupation, the Levantine state was a byword for the ascendancy of the Bush Doctrine. "It's strange for me to say this," the Lebanese Druze leader Walid Jumblatt told columnist David Ignatius in February 2005, "but this process of change has started because of the American invasion of Iraq. I was cynical about Iraq. But when I saw the Iraqi people voting three weeks ago, eight million of them, it was the start of a new Arab world."

Fast-forward to the present and then watch as the Cedar Revolution gets played in reverse. The White House issued a remarkable statement last Wednesday warning of "mounting evidence that the Syrian and Iranian governments, Hezbollah and their Lebanese allies are preparing to topple Lebanon's democratically elected government." That evidence includes recent threats on the lives of leading anti-Syrian figures, about a dozen of whom were assassinated last year. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has also promised massive demonstrations if his demand for a "national unity" government -- in which he and his allies would gain enough seats in the cabinet to exercise a veto -- is not met by the end of this week.

This could be scene-setting for another civil war, if the Lebanese have the appetite for it. Mr. Nasrallah's opponents, including the notorious Christian militiaman Samir Geagea, have put it about that if Hezbollah goes ahead with its demonstrations they will stage massive counterprotests and perhaps barricade the roads into Beirut.

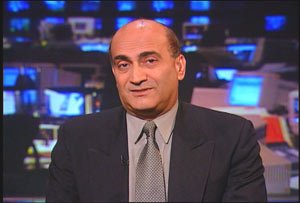

What would Mr. Nasrallah do then? "He's going to push the troops of others to bring about an incident," speculates Lebanese commentator Walid Phares of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. "He'll start a massive demonstration in front of [Prime Minister Fuad Siniora's] office and demand his resignation. He'll portray himself as the opposition. What he would love most of all is to have the media broadcast the downfall of the Bush-allied government."

That's one scenario, though it probably won't come to that: Mr. Nasrallah would prefer maximum autonomy within the country than actual responsibility over it. Instead, Lebanon's political classes are likely to settle on a compromise that would sacrifice at least one of the three most cherished goals of the Cedar Revolution. The first is disarming Hezbollah, as required by the 1989 Taif Accords and demanded by U.N. Resolutions 1559 and 1701. But that latter resolution, part of the cease-fire agreement arranged by Condoleezza Rice last summer, does more to shield Hezbollah from Israel than the other way around.

Second is a successful conclusion to the U.N. investigation into the murder of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. The investigation, led by low-key Belgian prosecutor Serge Brammertz, is said to be within weeks of wrapping up, and informed U.S. diplomatic sources expect that it will indict senior figures in the Syrian regime, including relatives of President Bashar Assad. But the indictments must be followed by a trial in Lebanon, which Mr. Assad is desperate to quash. Hence the Hezbollah power play: If Mr. Nasrallah and his allies can gain a third of the cabinet's seats, they can prevent the Hariri case from ever going to trial.

Finally, the Cedar Revolution was supposed to put an end to Syria's meddling in Lebanon. But that won't happen if at the end of this week's political negotiations the Lebanese government allows President Emile Lahoud, still and forever a Syrian puppet, to remain in office even as the country moves to early elections. Nor does it help that Mr. Assad continues to prove his worth to Mr. Nasrallah by serving as his main conduit of arms.

In all this, Hezbollah has been helped by the weakness of its domestic opponents. The Cedar Revolution demonstrated that Lebanon's anti-Syrian forces were a majority in the country. But those forces are fractious and unsure of themselves, and Mr. Nasrallah was able to draw down their support by striking a deal with the opportunistic Maronite leader Michel Aoun. Israel's incompetent military campaign last summer was another boon for Mr. Nasrallah, since anything less than his complete defeat in war was bound to embolden him politically.

Then there is the forthcoming report of former Secretary of State James Baker's Iraq Study Group, which is rumored to urge the Bush administration to re-engage Damascus diplomatically. In recent days Mr. Assad has been talking a blue streak about his willingness to make peace with Israel, a signal that he might be willing to play ball on that front and maybe in Iraq if only the administration lets him have his way in Lebanon.

The term for Mr. Baker's advice is "sell-out," and it is entirely characteristic of his past Mideast diplomacy. As an alternative, Mr. Phares argues that Ms. Rice should convene a conference of Lebanese NGOs in Washington as a way of bracing them for what he calls a "second Cedar Revolution." Also noteworthy is the internal Shiite opposition to Hezbollah: "The Shiite community never gave anyone the right to wage war in its name," Sayed Ali al-Amin, the Shiite mufti of Tyre, recently told Beirut's An-Nahar newspaper. With winter approaching and Hezbollah reportedly sharply cutting back on its reconstruction funds to homeless Shiites, there's an opportunity here to discredit Mr. Nasrallah and separate his organization from its religious base.

Saving Lebanon will require focus, nerve and imagination, qualities hitherto absent from Ms. Rice's tenure at State. Maybe if her boss loses his majority in Congress, he'll be less inclined to let the remainder of his legacy go down the drain with it.